His argument basically boiled down to the fact that the game was disingenuous. It was made to be profitable and still operates like pretty much every other military shooter out there, built around the same core positive psychology gameplay loops that reward kills. In the case of Spec Ops, though, the game's attempts to make you feel ashamed for reveling in these loops struck him as hypocritical and contrived to the point where it undermined the larger message of the game. For comparison, he held up Max Payne 3 as a good example of a game that uses extreme violence to call attention to the absurdity of the heroic power fantasies that practically all big budget video games are built around.

So first I'll explain where I'm coming from. I've already covered my feelings on Spec Ops (In brief: HOLY CRAP IT'S SO GOOD AND CHANGED MY LIFE AND EVERYONE NEEDS TO PLAY IT NOW NOW NOW NOW VIDJA GAEMS ARE SAVED), but Max Payne 3 is where things get a bit more complicated. I won't go in depth about all my problems with the game but suffice to say, I liked it a lot even though it didn't feel like a Max Payne game. There was practically no connection to the other games, and it felt instead like I was playing as Max's douchebag, nihilistic brother Mack. But that I could forgive, because the gameplay was very well done, with a bunch of rich environments and an intriguing story. But that's where the problems started for me.

Throughout Max Payne 3, the main character is presented as a drunk idiot who's blundered into a situation way over his head. His solution to these volatile and complex political intrigues is always "shoot them in the face". Max is very much presented as the bumbling American tourist, trying to parse through familial conflicts, violent city politics, and a seedy underworld, all situated in a location so exotic he doesn't even attempt to learn the language. There are a bunch of scenes of really gruesome violence, which, as my housemate puts it, force the player to step back and reassess how ridiculous all these things are. Case in point: every time you clear out a room, you're treated to a slow motion close up of the last enemy keeling over, with headshots yielding even more gruesome rewards and the player being able to slow down the view to really appreciate all that viscera spewing everywhere.

"So I guess I'd become what they wanted me to be.

A killer. Some rent-a-clown with a gun who puts holes

in other bad guys."

But when I was presented with this take on the game I was forced to reevaluate my view on it. Because after all, this is Rockstar we're talking about. They're one of the few development studios that has shown a consistent dedication to using the medium of video games to try and tell a story in addition to simply offering up cool gameplay. Beyond the stylistic choices, it's totally possible to look at Max Payne as a very subtle and wry satire about the absurdity of the idea that a hostile, complex situation can be fixed by one pissed off guy with a gun killing all the "bad guys". This also helps to make the super abrupt and seemingly dissonant ending go down a bit easier.

But if this was the creator's intent, then the bad news is they failed. The game got a fairly warm critical reception, but was by no means a smash hit. What's more, the majority of critics saw the game's plot as either an attempt to ape the style of such films as Man on Fire or as another instance of a game that's trying to be mature by presenting itself as gritty and hard-boiled. If there was a satirical or subversive element to the game, it passed right over the heads of most of the people who played it. By contrast, all people can talk about with Spec Ops: The Line is how brutally and effectively it deconstructs the modern military shooter.

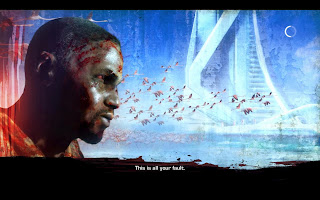

The game accomplishes this feat by making what it's doing very blatant. As the game progresses, the player is assailed with evidence that what they're doing is wrong, to the point where the loading screens start verbally attacking you. Another housemate said that while there are obvious parallels between the game and Apocalypse Now, one of the more striking areas in which the two differ is that in the film, the ending leaves a lot more up for interpretation. In Spec Ops, it is explicitly spelled out for the player what is going on and why they should feel bad. As my roommate would argue, this is where the disingenuousness creeps in, because the game still uses those core loops of kill and reward, then admonishes you for participating in them.

I'd argue this is why the game's message works so well. Though the conceits of Spec Ops' message (and even the twist at the end) aren't anything new, they are things that haven't been tried in video games before. The key strength of Spec Ops, for me, is that it realizes it doesn't exist in a vacuum. The Call of Duty series has made millions of dollars and is in turn played by millions. The games in the franchise come out annually and consistently break sales records. The series has spawned a host of imitators, all of which purport to provide an "authentic" experience that winds up resembling your standard Hollywood blockbuster more than anything remotely similar to actual conflicts occurring today across the world.

Why these games in particular are so successful is due to a number of reasons, and most of them probably are related to gameplay and multiplayer in particular. But as Film Crit Hulk points out, the single player campaigns shouldn't just be ignored. Spec Ops: The Line is bold enough to ask why we like these stories so much and why they're so popular despite the fact that they present a vision of both politics and warfare that is grossly distorted, sometimes horrifically so if you think out all the implications (look at how torture is presented in the Modern Warfare series).

Though this game was, like Max Payne 3, not particularly successful commercially, it was widely praised by critics. Even those who had qualms with the story and its execution praised it for what it set out to do, and the fact that it was willing to address these issues in a way other games clearly didn't want to. The innovations Spec Ops: The Line introduced in terms of what video game stories could be about resonated in a big way, though it's premature to say whether it will have a lasting effect.

So why did Spec Ops succeed at conveying a message that was widely acknowledged whereas Max Payne 3 was simply regarded as more of the same? As Ben "Yahtzee" Croshaw put it, a medium or art form can only be as good as the culture that surrounds it. At the risk of making really big generalizations, video games right now are very firmly divided into mainstream games concerned with providing entertainment and "art" games. There is very, very little overlap between these two areas. So when we see a game like Max Payne 3, which presents itself as an especially pretty and well-made shooter with a robust multiplayer heavily touted by the developers and a fairly absurd and contrived story, we take it at face value because we're accustomed to all that being the norm when it comes to big AAA games. When a game like Spec Ops comes along, a game that is very self-aware and that urges the player to examine what they're experiencing critically, we react in a big way, because even though that's a very old literary technique, it's one that hasn't ever been used so effectively in video games.

The net result of all this word-vomit? As I see it, it speaks to the fact that video games are such a new medium that there's very little context for really in-depth, cerebral criticism of them. We're still grappling with the fact that this medium, which many still regard as either "kid's stuff"or a simple distraction, has the potential to affect us emotionally and intellectually in ways other art forms can't. Though it might be easy to understand this concept on a basic level, the implications of what this could mean for video games as it becomes more prevalent throughout the development landscape are only just beginning to make themselves felt in really noticeable ways. Even though members of the video game community have been touting this sentiment a bunch in defense of the medium, the community at large clearly isn't yet accustomed to a mindset where, in the words of Film Crit Hulk once more, we stop asking what games can do "for" us, and more what they can do "to" us. In that respect, I stand by my assessment of Spec Ops: The Line. It might not be the most sophisticated work, but it serves a necessary purpose for the big budget video game industry in it's current state, holding up a mirror to the player and creator and asking them if this is really what they want.

No comments:

Post a Comment