If you are reading this blog, then you have seen this ad. That is just a statistical fact, and ordinarily I don't trust math, because it's performed by people who are interested in math, and therefore clearly have something deeply, intensely wrong with their brains. Those people should go see a brain doctor at once.

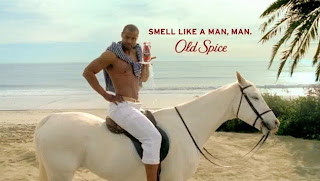

Anyway, that ad. It was just the first of many. It showed up 3 years ago and blew everyone away to such an extent that they're still going strong. All of these ads feature ridiculous effects and sharp writing that serve to get one message across clear as day: Use Old Spice and you will be the manliest of men. And we, the makers of Old Spice, know this.

It's that second part that is key to the success of Old Spice's marketing. Most other ads that take this tack, both before and after the revelation that was "The Man Your Man Could Smell Like", have tried to use the first part to varying effect. As an example, I would offer up every ad for pickup trucks ever made. It's a truism of advertising that you aren't just selling a product, you're selling an idea. When people make a decision to buy something they consider the act a sort of personal statement, and brands naturally recognize this. This is why successful marketing manages to tap into feelings that can transcend the obvious trappings of the product being sold. I don't watch sports, let alone soccer, but Nike has made tons of commercials centered around the game that I consider among my favorites of all time. This isn't just because of their impressive production values or the novel concepts they have as their premises. It's because they realize that soccer can be about so much more than just kicking a ball around a field. The ads are really about things like success being earned and not just granted, or how at the end of the day, our future is ours to determine.

Most ads, of course, aren't quite so high minded. Selling pick up trucks requires an emphasis on the fact that this truck is going to make you strong and powerful because it is big. That's about it. When they have done something similar to those Nike ads, they're still about how tough the people who buy (and make) these trucks are. Take a good long look at that commercial. It's selling an idealized vision of a lifestyle that has become marginalized in real life by agribusiness and gigantic factory farms, but the vision of a hardscrabble, salt of the earth farmer is so ingrained in the popular subconscious that the commercial can effectively use it as a shorthand for manliness, which they then link to the truck. The message is clear: buy a Ram pickup, and you will be as rough and tough as these grainy pictures we're flashing across the screen.

Old Spice, on the other hand, realizes there are more and more people becoming more aware of the tricks of the trade of marketing. The solution to this conundrum isn't self-deprecation: people aren't going to buy something if you tell them it's crap, because you're making it, so you would know better than anyone. The solution, rather, is to go in the exact opposite direction as hard as you can. Underlying all of the Old Spice commercials is the tacit acknowledgement that yes, the idea that a body spray can grant you the physique of a god is ridiculous. But that idea is also so hilarious that it becomes ripe for parody in a cavalcade of outrageous and hilarious commercials.

Old Spice ads don't just grab people's attention through their overload of images and crazy concepts. They speak to a self-awareness that is permeating a lot of the media that absolutely saturates our culture. Their philosophy is to take the implicit claims of other "manly" marketing campaigns and make them explicit, which manages to both defuse and win the argument at the same time. Ram can't claim with a straight face that buying one of their trucks will imbue you with the spirit of centuries of wizened cattle ranchers, but they can very heavily imply it. Old Spice explicitly says that using their body spray will enable you to win all the first place medals and live forever through your line of premium table crackers. My roommate once noted that a lot of commercials are just weird from an objective standpoint, because they're set in a world where the product being advertised is the most important thing in the life of the characters involved. Having bad teeth in a commercial for toothpaste is basically asking to be thrown in jail for making children everywhere burst into tears every time you open your ugly mouth. Old Spice takes this to its logical conclusion by making the men who use it in commercials into mythical heroes who can turn tickets into diamonds because they smell so good.

You just can't beat that. Being ridiculous on that same level for your product won't really work, because Old Spice already did that (and did it pretty much perfectly), and most other traditional ads pale in comparison. The Old Spice ads are brilliant because they manage to be almost perfect satires of a lot of other commercials, and even if you don't catch on to this, they still work because they're so well made and written. Old Spice has managed to both deconstruct and reconstruct the idea of marketing products as "manly", a feat that could obviously be accomplished only by a man who smells like freshly cut wood being used to build a boat for conquering the deadliest ocean.

Okay, I lied. Dos Equis does it well, too. You know what, forget everything I just wrote up there. The key to selling products is a deep voice. Get a dude with a deep, powerful voice, and everyone will buy whatever you're selling. There, done. Marketing: Solved. You're welcome, New York.